In the spring of 1876, as the United States celebrated its centennial and cities from Boston to St. Louis buzzed with parades and patriotic fanfare, a quieter kind of revolution was taking shape, one with leather balls, hand-cut bats, and handbills pasted to wooden fences. It was called the Century League, and it was the dream of a war-tested engineer from Illinois who believed that base ball could be more than just an idle pastime. He believed it could be an institution.

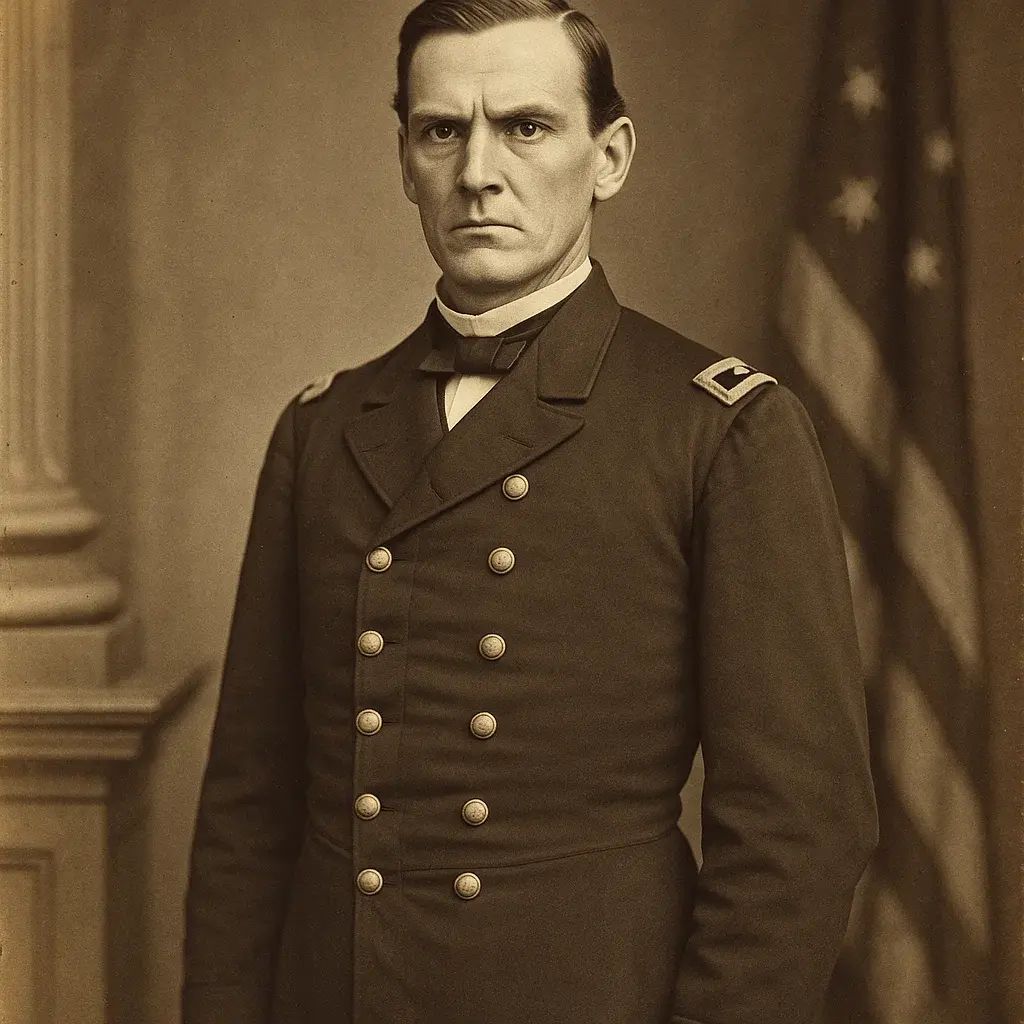

That man was William Washington Whitney.

Born in Springfield, Illinois in 1833, Whitney had the kind of upbringing that molded men of action. The son of a surveyor and grandson of a Revolutionary War soldier, Whitney earned his appointment to West Point in 1851 and graduated four years later with a commission in the Corps of Engineers. Quiet, serious, and detail-minded, he was a man better suited to planning bridges than making speeches. But when the war came, he didn’t hesitate.Whitney served with distinction in the Western Theater, fighting under Ulysses S. Grant and later William T. Sherman, building pontoon crossings and reinforcing battle lines from Shiloh to Vicksburg to Atlanta. By the time he mustered out in 1865, he wore the eagle of a Colonel and had the ear of some of the most powerful men in uniform.

He also had a friend, a rare thing in wartime, named Jefferson Edgerton.

Edgerton was an unusual figure: a Virginian by birth, a loyal Union man by choice, and a year behind Whitney at the Academy. Where Whitney was deliberate and plainspoken, Edgerton was cool-headed and eloquent, an artillery officer whose courage at Shiloh and Chickamauga earned respect even from skeptical Northerners. While many of his Southern-born peers cast their lot with the Confederacy, Edgerton stayed. “I took my oath at West Point,” he later said. “It was not made in jest.”

After the war, the two men went their separate ways, Whitney back to Illinois, Edgerton to Philadelphia. Whitney took a position with a Midwestern railroad, applying his engineering skills to the postwar infrastructure boom. Edgerton opened a leather goods and sporting supply shop, his passion for base ball, cultivated among the camps and cannon, finding new life on the streets of a thriving industrial city.

Unbeknownst to one another, both men drifted into base ball from opposite ends of the map. Whitney, ever the organizer, began gathering the disparate barnstorming clubs and fledgling nines that dotted the Midwest. By 1874, he was convinced that only a formal league, with structure, integrity, and financial stability, could give the sport a future. He called it the Century League, in honor of the coming national milestone. The idea: eight teams, professionally operated, playing a set schedule with a league office in Chicago.In the spring of 1875, he called a meeting of club representatives to take place at the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago. Seven men arrived, rough-edged promoters, gentlemen of fortune, and businessmen of varying ambition. But it was the eighth man who gave Whitney pause: a well-dressed Philadelphian with a cavalryman’s mustache and a knowing smile.

Jeff Edgerton.

The reunion was immediate. “You might have warned me you were founding a league,” Edgerton quipped. Whitney only laughed. “You might have warned me you’d be running a club.”

Together again, this time in peace, the two men helped shape the first season of organized professional base ball in American history.The eight original clubs paid a $500 admittance fee, a princely sum for the time. But money wasn’t the only thing these men brought to the table.

From Boston, Ezra Barzillai Whitcomb, a stern dry goods magnate and moralist, brought his Pilgrims to the fold, seeing base ball as a civilizing force for the masses. In Brooklyn, former dockworker turned labor kingpin Frank Braddock formed the Unions, a workingman’s club with a blue-collar edge.Chicago belonged to Whitney himself. The Chiefs were his flagship, his blueprint for what a proper ball club should be. But just across the Ohio, James Pembroke Tice had other ideas. The Cincinnati Monarchs were the creation of a soap baron with a gift for self-promotion and a stubborn streak that clashed almost immediately with Whitney’s iron sense of order. “If anyone’s building a base ball empire,” Tice said, “it ought to be me.”Detroit’s entry, the Woodwards, came courtesy of Horace Delano Sutherland, a conservative shipping baron more interested in balancing ledgers than winning games. New York was represented by the Knights, a stately club bankrolled by Wall Street heir Lucius Belmont, whose polo connections and social calendar gave the league a touch of polish.

And in St. Louis, German-born brewer Adolph Fuchs offered something else entirely: beer. Fuchs got around Whitney’s “no alcohol in ballparks” edict by installing a full beer garden behind the grandstand, accessible via tunnel. Technically separate from the seating area, it became the liveliest, and loudest, section in the Century League.

By April 1876, with uniforms pressed and timetables drawn, the Century League launched its inaugural campaign. For base ball fans between the Mississippi and the Atlantic, it was more than just a game.It was structure. It was pageantry.It was summer, finally made official.And it all began with a West Point engineer, a Southern loyalist, and the belief that America’s pastime deserved a league worthy of its name.